Part 3 of a 6 Part Series

This is the third of a six-part series. The reader is strongly urged to visit these websites and study what is discussed in these articles in order to make an informed decision.

Part one covered data collection in the Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy (CWCS) which was used to create the State Wildlife Action Plan (SWAP) for species and habitat protection. In part two ecosystems and its components were covered These topics create the foundation for corridors and connectivity.

My family’s connection to Island Park began with my paternal grandfather who was an engineer for Union Pacific. His route traveled from Pocatello, through Big Springs, and on into Montana. When old enough, my father joined him on these trips and was dropped off at Big Springs, where he spent his time fishing until his father picked him up on the way back. As he grew into a man he spent more time in Island Park camping, fishing, and hunting with my maternal grandfather, learning the area like the back of his hand. His connection was so strong the first thing he did after basic training was to go there on his two-week furlough, taking his very pregnant wife along, before going to battle in WWII. Following the war every minute he could find was spent in Island Park. Waiting for summer wasn’t enough, winter had to be conquered. He often bragged that he was the first person to snowmobile into his cabin, on what was possibly the most pathetic excuse for a snowmobile, which had to be started with a rope pull, and whose speed was that of a turtle. My story is very similar to others who have a strong heritage and connection to this land. My family started with the railway corridor, connecting us to the Island Park community, now primarily by highways. Wildlife also has its migratory corridor which still exists today. These connections are meant to stay and not be environmentally engineered into something different, or usurped into another entity.

Varying greatly in size, shape, and composition, corridors can be described as routes or land tracts used by migrating animals, land designated for specific purpose such as highways like the US 20 Corridor, or they connect “fragmented” patches of habitat. Corridors are seen as a way to increase connectivity, such as transportation or between patches of fragmentation supposedly caused by humans due to different types of land development. Scientists often call this the “anthropogenic” effect, meaning fragmentation is the result of human influence on nature, which NGOs and scientists describe as disruption and “barriers” for plants and animals to survive. They believe corridors, especially protected corridors, provide an unbroken path of suitable habitat and safe passage, if it weren’t for humans disrupting it, and connectivity. Three types of corridors follow.

Biodiversity corridors are areas of vegetation that allow animals to travel from one patch to another, providing shelter and food for different species. Blaming anthropogenic activity, scientists believe that all species become isolated and unable to migrate as intended because of human “barriers”. Elk don’t care if they cross your property to get where they are going, they and other grand creatures do it all the time. The agenda underway is identifying biodiversity corridors for conservation to restrict or mandate a full ban on all “anthropogenic” activity, thus ensuring species movement between patches, which already exists now. Island Park residents know differently, we have co-existed with all animal species and their movement from before the time of my father.

Wildlife corridors are tracts of land allowing wildlife to migrate for food, shelter, and mating between habitats with migratory paths as an example. Wildlife use biodiversity corridors during their journey for necessary food and shelter. Elk, moose, and other migratory species in Island Park have migrated along these paths for centuries. Who in Island Park has not watched them on their land as they move through?

Riparian corridors have everything to do with water. This includes wetlands, marshes, ponds, streams, creeks, springs, and lakes. Water species such as fish and beavers, and plants that thrive in wet environments, are all included in these corridors. These corridors naturally intersect with biodiversity and wildlife corridors and are often extended by scientists to include buffers, zones, and land for restricted use. Everything is connected to water.

However, scientists believe anthropogenic activity is destroying natural corridors and corridors should be sewn together for connectivity, with no “disruption” or “barriers”. NGOs, scientists, and the government want us to believe they have the knowledge and authority to artificially engineer corridors. Sorry, Mother Nature beat you to it, her corridors already exist naturally, scientists are only artificial engineers and will never surpass Mother Nature. It is disheartening to watch scientists attempt to environmentally engineer land and corridors that are already perfect with roads and private land not disrupting migration paths, the paths are still there.

In 2008, the Western Governor’s Association (WGA) participated in this agenda, signing a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with the DOI, DOE, and Department of Agriculture to “coordinate and identify key wildlife corridors and crucial wildlife habitats for uniform mapping and recommendations on policy options and tools for “preserving those landscapes”. Did Governor Otter contact you for your opinion? How about those other governors making decisions for Idaho?

While the USDA touts the benefits of corridors, there are also studies that have been conducted on the detrimental effects. Because species are crowded into an artificially-designed landscape it is often an invitation for invasive species, whether plant or animal, and increased predator behavior. There is also the belief that fragmentation lowers genetic diversity if one herd can’t get to another. Elk have been moved around to different locations by scientists for experimentation on their genetic diversity and divergence (mutation). What impact does this have on Elk and the natural order of the environment which is subject to natural laws, not human?

Another aspect to corridors is conservation easements. According to the Kansas Natural Resource Coalition, “Often CE properties are enrolled into programs for introduction of endangered species or development of ‘corridors,’ an initiative itself that can profoundly affect communities, industry and private lands. The introduction of endangered species substantially impacts the productivity of neighboring properties.” This is the intention of SWAP, identifying species of greatest concern and habitats needing protection. Something to keep in mind if you are asked about placing your land into a conservation easement. Your property may have already been identified for conservation “value” which might contribute to an effort for corridor conservation.

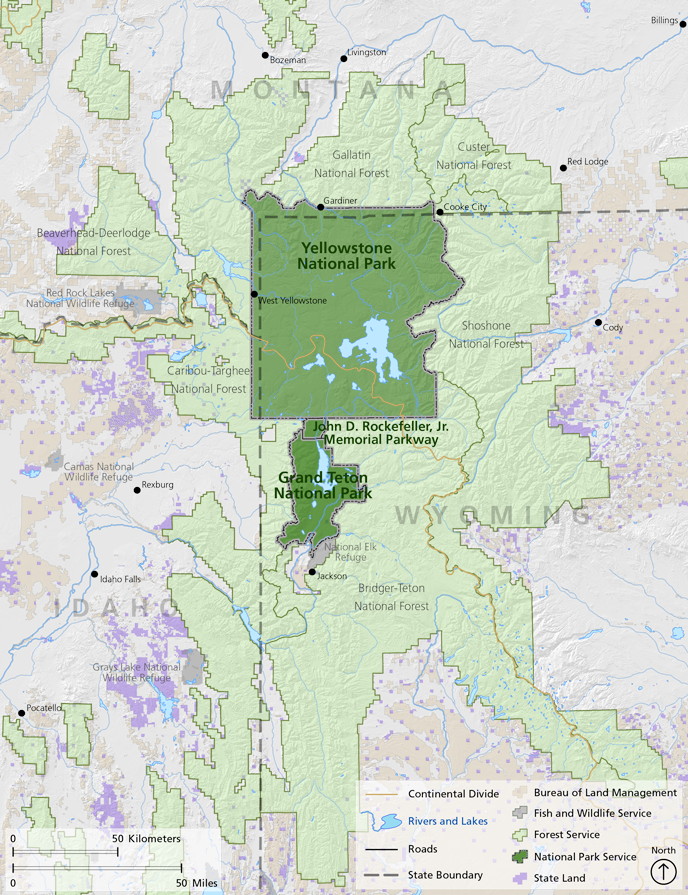

These corridors, and all their components, lie within an ecological boundary known as an ecosystem. Ecosystem can be defined as “a system, or a group of interconnected elements, formed by the interaction of a community of organisms with their environment.” Scientists have included Island Park in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE). The GYE boundaries are shown in this map.

The American Wildlands “Corridors for Life” program from 2007, Center for Large Landscape Conservation (CLLC), Defenders of Wildlife, Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) with whom the new road ecologist Renee Seidler is connected, and the USFS focus on creating wildlife corridors for connectivity while the North Pacific LCC, Washington State University, and GNLCC focus on riparian connectivity. Using corridors for connectivity is published in their agendas. The scientists who conducted studies in Island Park even admit that wildlife overpasses are needed for connectivity but have not disclosed that to the public. Island Park residents are provided only information about wildlife vehicle collisions to justify the need for wildlife overpasses while the bigger threat, changing the environmental structure, culture, identity, ownership, and heritage of Island Park, is omitted.

Gary Tabor, founder of the Center for Large Landscape Conservation (CLLC) and who mingles with all the local initiatives, worked with Va. Rep Donald Beyer (D) on H.R. 6448 (114th): Wildlife Corridors Conservation Act. Although not enacted in 2016, there are plans to reintroduce it again this year. This bill would create a “National Wildlife Corridors System” which would mean federal law for corridor designation, much like a national monument designation. Island Park residents don’t want to be a federally designated anything. Also not welcome, a Virginia representative making decisions that would potentially affect Island Park.

The new ITD “road ecologist”, Renee Seidler, participated in a migratory study on Pronghorn in Wyoming. While the WCS claims the “U.S. Forest Service established the nation’s first federally designated wildlife corridor” in 2008, the truth is somewhat different.

It was not a declaration of the “first” federally designated corridor, it was a forest plan amendment that merely allowed “continued successful pronghorn migration.” Amending the “…Bridger-Teton National Forest Land and Resource Management Plan by designating a Pronghorn Migration Corridor…”, it added the following standard, “All projects, activities, and infrastructure authorized in the designated Pronghorn Migration Corridor will be designed, timed and/or located to allow continued successful migration of the pronghorn…”, while not constraining “…activities on private land…” within the forest boundary. The report also states, “…activities currently authorized by the Forest Service within the corridor coexist with successful migration…” such as grazing, and concluded that no changes were needed for grazing or infrastructure. So, the Bridger-Teton National Forest Supervisor, in a NEPA Environmental Assessment phase, casually gave a name to a section of forestland that already existed, the NGOs then exaggerating it into some grand event which didn’t exist. There was no congressional act or official designation, no state declaration, no proclamation, nothing.

The BLM is not part of this forest plan amendment. “The amendment just signed does not protect the entire pronghorn migration – it applies only to 45 miles of the migration corridor located on Forest Service lands. The remaining 30 miles of the migration route occur on private lands and areas managed by the Bureau of Land Management, BLM.” Seasonal protection of the Pronghorn is provided by the BLM but there is no federally designated Pronghorn corridor as the NGOs would have us believe.

Now, this exaggerated claim has been stretched to declaring the “Path of the Pronghorn” as the “only federally-designated wildlife migration corridor in the United States”. It is misleading and dishonest. Beware, the WCS is watching Craters of the Moon stating, Pronghorn are “…restricted by mountains, fences, a highway, and fields of jagged lava from Craters of the Moon National Monument and Preserve…”. How do those Pronghorn migrate every year in spite of these restrictions and natural landscapes?

Using the Elk migratory path is just the first step, next will be a demand to protect the biodiversity corridor, then a riparian corridor, any corridor will be used to continue sewing them together for control over the land while describing it as connectivity, and for a “seamless” integration into the GYE. They don’t care about the Elk, they are only interested in using them to take land for their agenda.

Island Park residents have “connectivity” with their land as my father did, and those before him, crossing different “corridors” that allow us to remain “connected” to our land. We get it, we know the abundance of gifts that are provided. But there is no justification for taking what already is a blended and pristine area, breaking it into ecological categories and corridors, violating state and county sovereignty, then creating plans to alter it. This misrepresents the reality that Island Park is already connected, in every way.

The only disconnection is the one that is fabricated by scientists, NGOs, and the government. It is their imaginary utopia being imposed on Island Park residents, and those poor Elk. The greater plan by scientists and NGOs is putting Island Park into full conservation status without your consent, creating artificial landscape designs and boundaries, convincing you that corridors aren’t connected because a road or your house is in the way, telling you connectivity is needed for integration into an ecosystem where it already exists, and destroying our God given right and legal authority as Fremont County residents to control how land is used.

From the Declaration of Independence: It becomes necessary for one people to assume:

“…the separate and equal station to which the laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them…”

“…that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, governments… deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed…” The consent of the governed has not been given for these plans.

Part 4 in this series will discuss connectivity, who is involved, and its implications.